To understand Communications, we will examine the unconscious mind and implicit bias, and also explore why understanding implicit bias is important not only for effective communication, but also for identifying possible interventions. We will introduce effective ways to talk about race and about issues that have been racialized.

About 2% of emotional cognition is conscious, with the remaining 98% of emotional cognition unconscious. This means, our unconscious mind has significant influence on our positions on critical issues. For example, the majority of Americans believe in equality and most Americans believe racial discrimination is wrong; overt bigotry persists among only 10% of citizens. However we continue to make decisions that reinforce racial inequity. How can this be?

Power of Unconscious Mind

To have a clearer sense of how the mind works, try these tests:

A. Reading out loud, what colors are the following lines of text?1

B. Video Awareness Test: How many passes does the team in white make?

[WATCH: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oSQJP40PcGI]

Conscious values and beliefs play only a small role in how we process information and make decisions;2 many biases that affect behavior and decision-making reside in the unconscious mind. Thus, people who consciously value racial equality can act and make decisions based upon racial biases without even being aware that they have any biases at all. When a person’s actions or decisions are at odds with their intentions, we call this Implicit or Unconscious Bias3.

Because racial biases permeate our society, racial anxiety can be triggered without making any explicit reference to race. For example, first Ronald Reagan and later Bill Clinton, used the term “welfare queen” to refer to a negative and highly racialized stereotype of unwed, African-American mother. Using this negative stereotype exacerbated and stoked racial anxiety that government programs were helping “them” rather than helping “all of us”. Despite the fact that the greatest number of welfare beneficiaries are racially white, by speaking in racially coded terms, Reagan and Clinton both eroded support for government programs by deepening the sense that there is a racial other and by reinforcing the misconception that these programs were designed to help, or worse still were being exploited by, that racial other.

This is one example of how racial anxiety is used as an effective and damaging political tool without ever talking about race explicitly. Because this is so common, to not talk about race or avoid talking about race is, in effect, to talk about it to the unconscious mind. Since our unconscious mind influences our positions on critical issues, if we don’t learn to talk about race in constructive ways, and in ways that suggest alternative responses to unconscious, societal anxieties, we essentially cede the conversation to unfounded fear and anxiety.

- Variation on the Stroop Test.

- Americans Values Institute, (2009) What is Implicit Bias? Retrieved from http://americansforamericanvalues.org/unconsciousbias/

- ibid

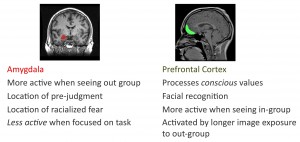

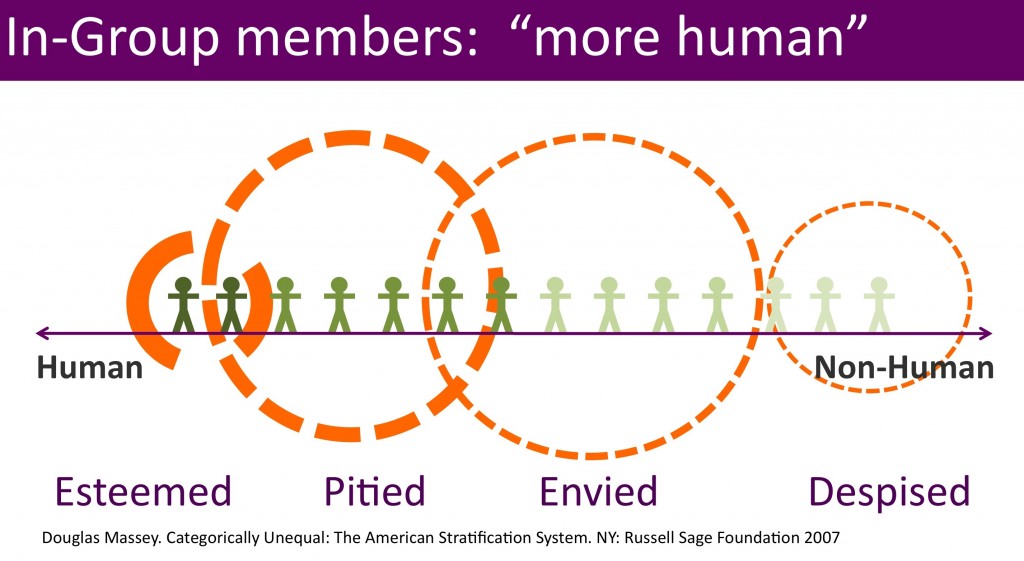

Neurology for Activists

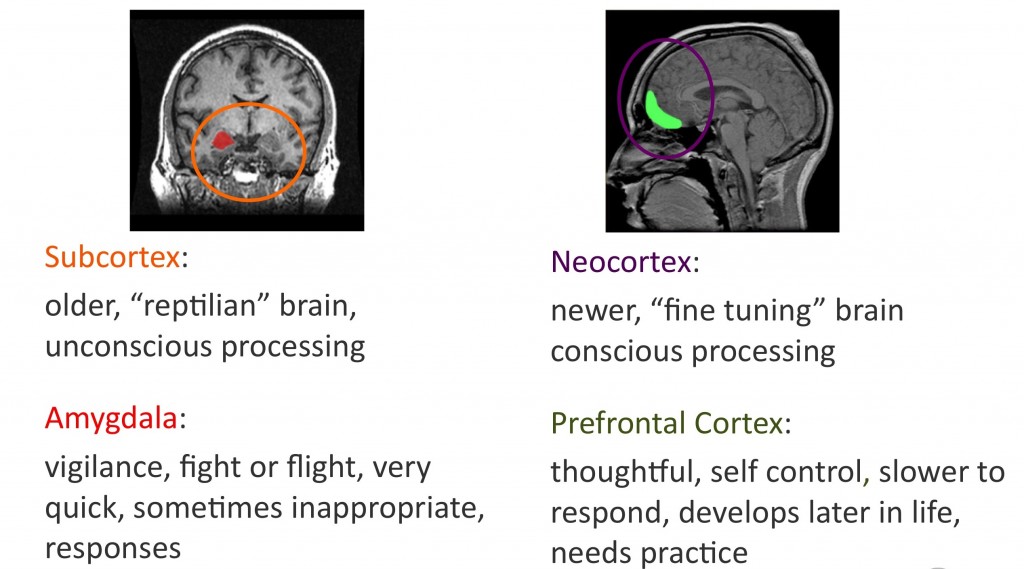

Different regions of the brain serve different purposes. The limbic system categorizes what we perceive. The amygdala, a part of the limbic system, perceives threats and initiates rapid fight or flight responses. In survival situations, this is effective; for example, when in the path of a speeding car, quick perception of threat and initiation of a flight response can save us. Recent brain studies, however, show that the amygdala also becomes highly active when it perceives people associated with out-groups, and responds as if encountering a threat or hostility1. Amygdala response is thus in alignment with unconscious racial stereotyping or biases. Since perception of in and out-group status is shaped by the culture and society that a person lives in, these biases are not fixed nor are they individual.

The prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for rational thought, develops later in life and reacts much more slowly than the amygdala. The prefrontal cortex is active when we are being thoughtful, exert self-control, solve problems and process our conscious values. It is also active in facial recognition, when we see images of people we identify as “in-group”, and when we have longer exposure to images of people perceived as belonging to out-groups.

Because the brain is malleable, with practice, the prefrontal cortex can develop the ability to make determinations that lead to appropriate reactions. For example, it is sometimes difficult for people to differentiate people in racial groups to which they do not belong or have had little contact. However, with practice, one can learn to differentiate and therefore recognize specific individuals, for example, who they have met.

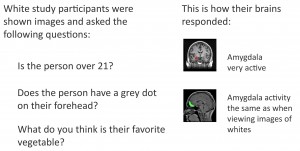

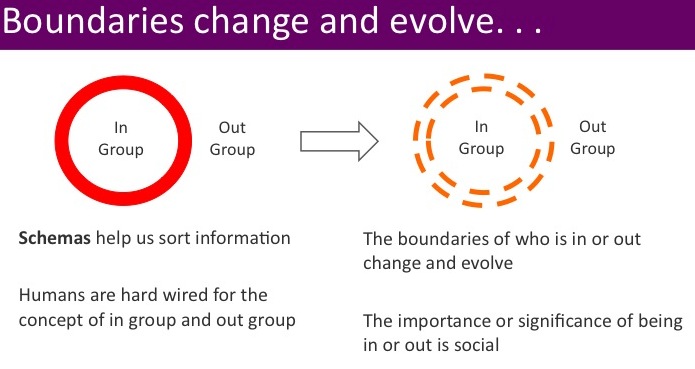

While we are hardwired to rapidly categorize in-group vs. out-group, we are soft-wired for the content and meaning assigned to those categories. Schemas, such as black/white, young/old, male/female are cognitive structures that help us make decisions quickly2. Though schemas are unconscious and, as a result, we are largely unaware that they exist, the meanings attributed to these schemas are culturally derived. For example, when you meet someone the mind very quickly and unconsciously assigns that person to a racial category, which then triggers all of the implicit and explicit meanings culturally associated with that racial category, or racial schema, and thus shapes your subsequent interactions3. However, depending on what you ask someone to notice about another person, his or her brain will respond differently.

For example, if you ask a white person if the person pictured is over 21 years old and the image shows a black person, the part of the brain associated with anxiety (amygdala) will be activated. If, on the other hand, you show the same image to the same person but ask instead what they think the person’s favorite vegetable might be, the part of the brain associated with thoughtfulness (prefrontal cortex) is activated and the amygdala is quiet. This affirms that the mind focuses on what it is asked to focus on, and suggests that it is possible to counter the effects of implicit bias and, therefore, reduce the impact of racialized anxiety on decision-making.

A growing body of research suggests that discrimination and bias are a collective phenomenon. That is, bias is social, and is not limited to isolated individuals. For example, tests designed to evaluate bias reveal implicit bias against nonwhites is pervasive even among members of stigmatized groups4.

In effect, implicit bias is a bit like bacteria in water. Just because you can’t see it, doesn’t mean that it isn’t there and doesn’t need to be dealt with. And just as we would not rely on managing bad bacteria in water on an individual basis, but would rather take a collective public health remedy, we should think similarly about implicit bias5. In the next section, we explore strategies and mechanisms to make these unconscious processes conscious.

- Dalai Lama & Cutler, H. (2009) The Art of Happiness. (10th Anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

- Kang, J. (2005) The Trojan Horses of Race. Retrieved from http://jerrykang.net/research/2005-trojan-horses-of-race/

- Americans Values Institute, (2009) What is Implicit Bias? Retrieved from http://americansforamericanvalues.org/unconsciousbias/

- 94 California Law Review (2006), p. 957

- Kang, J., & Banaji, M. (2006) Fair Measures. Retrieved from http://jerrykang.net/research/2006-fair-measures/

Implicit Bias in Problem Analysis

Implicit bias challenges the “colorblind” frame. Our current physical, social and cultural opportunity landscape informs not only our conscious experience, but also our unconscious experience. Since we are not able to know our unconscious biases, by definition, implicit bias gets in the way of our ability to even ask the right questions about the causes of differential outcomes.

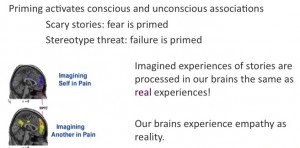

For example, a common prejudice is that women aren’t good at math; because that prejudice is prevalent, many women choose not to take math classes, and thus the prejudice itself contributes to outcome. Moreover, women’s internalized fear of fulfilling a stereotype, ‘stereotype threat’, correlates with lower math test scores among women1.

A common justification for dependence on “colorblind” high school and college admissions based on test scores is that it rewards individual merit. For example, we often hear variations on the assertion that because Black students perform less well than white students on standardized tests, low numbers of Black students in elite institutions that rely heavily on test scores is justified. While it is factually correct that Black students have lower test scores, a Structural Racialization analysis, makes visible the connections between housing, concentrated poverty, under-resourced schools, and test outcomes, not to mention bias embedded in the tests and the impact of stereotype threat on test takers.

The Structural Racialization analysis enables us to demonstrate the impact of institutional arrangements and policies on group outcomes: where discrete systems interact to yield cumulative effects. Pairing a Structural Racialization analysis with an understanding of implicit bias, we are more likely to diagnose the problem accurately and identify effective interventions.

Questions we can ask ourselves that have the potential to help us be more effective in identifying the source of a problem include:

- What are prevalent biases and stereotypes that impact your issue area?

- Do any of these biases prevent you from seeing the structural, non-individual, basis of the outcomes?

- What do structural racialization and implicit bias suggest for identifying problems and developing solutions in the work that you do?

- Steele, Claude. Whistling Vivaldi: And Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2010. Print.

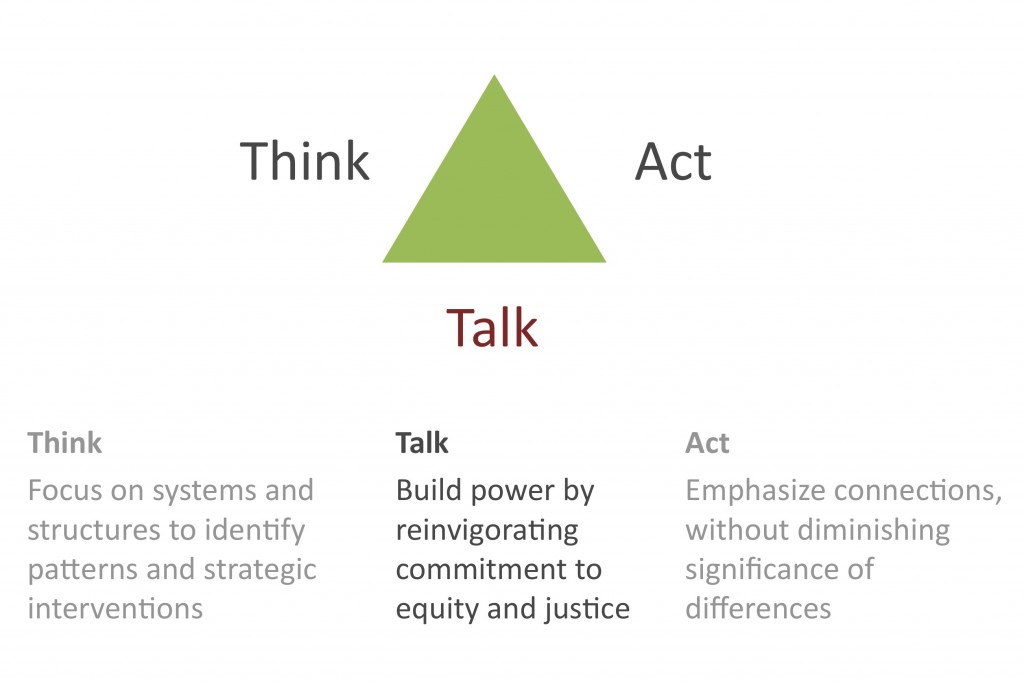

Communication & Implicit Bias

People, individually and collectively, thrive on making meaning. Categories such as race, which are used to create social ‘others,’ and give social, economic and political significance to those categories, constantly change and are reconfigured. Language and messaging contribute to shaping reality and the perception of reality by impacting meaning. Framing, the mental filters used to make sense of the world, and priming, exposure to a stimulus that influences response to a later stimulus, also impact how information is processed in both the unconscious and conscious mind.

Research on implicit bias, automatic—and therefore unconscious—prejudice that is often inconsistent with conscious values, has important implications for how we approach communication. In order to communicate effectively about an issue, not only do we need to ask what people think, but also, we need to understand the processes behind how people think.

When telling a scary story, a storyteller not only needs a scary plot, but also, benefits from understanding how to invoke fear, for example, by priming their audience with scary images. Also, a good storyteller knows that imagined experiences are processed by our brains in the same way as real lived experiences, and so expects their listeners to be appropriately impacted.

Recent research suggests that it is possible to develop messages that both reinforce our conscious values while also addressing unconscious biases. Paying attention to both conscious and unconscious decision-making supports people’s ability to make decisions based on their conscious values, rather than based on their unconscious biases1. Drew Westen writes, “people act on their conscious motives when they are focusing their conscious attention on them. Conscious motives can override unconscious ones, as when we remind ourselves to be tolerant, compassionate, or fair-minded when we have just met someone who has triggered a stereotype. But conscious motives only direct behavior as long as they are conscious2.” In other words, egalitarianism is a skill people can learn with support and with practice.

To not talk about race is to talk about race. Race appears in the media in multiple ways. For example, consider the media discussion of Arizona’s immigration law SB1070, which would make the failure to carry immigration documents a crime and gives the police broad power to detain anyone suspected of being in the country illegally3. In the best cases, the explicit discussion uses race neutral language, but even in these cases, the visual and implied discussion points to racialized groups of people who are the targets of the law. In this way, media legitimizes the practice of racial profiling, even though many, if not most, people who “fit the profile” are legal residents or citizens. Moreover, the media side steps examining systemic circumstances that motivate people to leave their families and migrate in search of work.

Research shows that suppressing or denying prejudiced thoughts can actually increase prejudice rather than eradicate it. Since media tends to reinforce negative stereotypes, researchers have tried and found that repeatedly exposing people to admired African Americans helps counter pro-white/anti-black bias. Similarly, an even more productive strategy is to show both admired African Americans and infamous whites4. It is important to use images and stories that counter negative stereotypes and reinforce a vision of shared prosperity.

This is the environment in which we work. It is not “race neutral”. The question is not if we should talk about race, but how we should talk about race. To change implicit biases, we need to be aware of societal implicit bias, provide stories, images messaging and language that counter implicit bias, and engage in proactive, cultural and structural change.

Talking about race can be difficult. Talking about race effectively takes practice. Why is it difficult to talk about race? Race is difficult to talk about because race itself is complex and is linked to individual and national identity. As a society, we lack shared knowledge and information about how racialization has evolved over time for different groups of people and what the consequences of racial inequality are for all groups of people. Moreover, the United States has a long history of violence, repression, and injustice directed towards people of color and towards people, of all races, who speak up against injustice. Talking about race can also surface feelings of resentment, guilt and hostility. Anyone who speaks about racism runs the risk of being labeled a racist—by both people who are for and against ending racism. And, of course, talking about race requires practice. How do we talk about race so that we are able to actively envision a democracy that includes everyone rather than one that includes only a select entitled few?

- Kang, J. (2005) The Trojan Horses of Race. Retrieved from http://jerrykang.net/research/2005-trojan-horses-of-race/

- Westen, D., (2007) The Political Brain: The Role of Emotion in Deciding the Fate of the Nation. New York, NY: Public Affairs. p. 226.

- Archibold, Randal C. (2010) “Arizona Enacts Stringent Law on Immigration”, The New York Times, April 23, 2010.

- Joy-Gaba, J.A., & Nosek, B. A. (in press) The Surprisingly Limited Malleability of Implicit Racial Evaluations, Social Psychology